From September to October 2025, the exhibition Computational Poetry was held at the NEORT++ Gallery in Bakurocho, Tokyo. Works by five groups of artists were displayed here. While this exhibition was themed around “computers and poetry,” it wasn’t about “using computers to create poetry.” Most of the works were created through computer programs—that is, code—and prompted contemplation about what poetry is and what language is. Here, programming languages were used not merely as tools, but as special materials for thinking. The distinctive feature of these works is that they contain analyzable thoughts and memories within the works themselves. Each piece possesses an intensity that allows for infinitely deep exploration, and one could certainly consider their connections to art history, poetry, and historical contexts of art. However, I believe the purpose of this exhibition was not that, but rather to discover new words from here.

I was involved in this exhibition both as one of the co-curators and as one of the participating artists. My motivation stemmed from a conviction that something was missing from the widely recognized history of computer art, and a desire to excavate it. However, once I actually began searching for works, that desire was tormented and crushed by the question of what it means to not be confined to existing fields or concepts. This exploration was contradictory from the start—things without names cannot be searched for in the first place. In other words, I began to realize this was work about creating concepts and names. With the great help of co-curator Shono-san, including the ways things didn’t go according to initial expectations, pieces came together for this exhibition—many of them new works—as a result influenced by my own intuition and conviction. To be honest, my first impression upon viewing all these works was that they seemed like quite disparate pieces with different orientations. However, the deeper I came to know about the works, including through writing this article, the more I felt new common layers emerging that I hadn’t seen before. Sharing that sensation—that is what this article aims to achieve.

Hai-Tech by Wen New Atelier (Kalen Iwamoto & Julien Silvano)

Wen New Atelier is an artist couple consisting of French artist Julien Silvano and Japanese-Canadian artist Kalen Iwamoto, who explore the boundaries of art, language, and technology.

Hai-Tech is a device that continuously generates random combinations of kanji characters commonly used in Japanese haiku and classical poetry with kanji frequently used in the technology domain. The kanji characters keep changing like a slot machine, occasionally interspersed with noise-like symbolic characters, before coming to a stop. The generated two-character kanji combinations prompt us to consider what these compound-word-like formations might mean. After 10 seconds pass, the next combination begins generating. Below the kanji, translated English words are displayed. The code is written in Python, and they call this work computational poetry. While the idea of generating compound words or sentences through such random combinations has existed for a long time, the distinctive feature of Wen New Atelier’s work lies in presenting the process itself with a contemporary sense of temporality. The combination algorithm is remarkably simple. This is because what the work emphasizes is not the algorithm itself, but rather the process of the algorithm’s execution and the thoughts it triggers within the viewer. This work also explores the identity of Kalen Iwamoto, who has lived across multiple different linguistic and cultural spheres—Japan, Canada, and France. The selection of kanji and the occasional sense of incongruity felt in the kanji-to-English translations direct our awareness to what constitutes our taken-for-granted sensibilities in the Japanese we normally use. It is exceedingly environment-dependent, and our sense of language is something fragile and ephemeral that can be easily shaken by such a simple algorithm.

《Hai-Tech》by Wen New Atelier (Kalen Iwamoto & Julien Silvano)

Data Waves in the Rising Sun by Wen New Atelier (Kalen Iwamoto & Julien Silvano)

Data Waves in the Rising Sun is a work that continuously deconstructs and reconstructs the beautiful texts describing scenes of light and waves from Virginia Woolf’s literary work The Waves through code-created algorithms. The Waves takes a form that could be considered somewhere between prose and poetry, and the author herself called it not a novel but a “playpoem.” This work by Wen New Atelier might also be understood as a new form of literature that doesn’t fit into existing genres. First, this work quotes tens of thousands of characters of text from “The Waves.” After randomly rearranging these words, it triples each word, extracts words for each line according to screen size, and adjusts the spaces between words to achieve justified alignment. While the justified alignment gives a literary impression, a monospaced font commonly used in programming environments has been chosen. However, since the spaces between words are adjusted rather than monospaced, it may give a slightly strange sensation to those familiar with computer fonts. The randomly created text updates every 200 milliseconds. At this speed, it’s almost impossible to read the displayed text as sentences. Only fleeting impressions of individual words remain, and what we see is like continuously flowing waves—a digital nature created there. Considering the number of quoted words, an almost infinite number of combinations occur. Thinking this way, this is no longer quotation but poetry creation. Yet it is made from nothing more than a beautiful but extremely limited length of text. Condensed within it is our process of creating sentences, presenting a contemporary answer to the question of what literature is. And through the gap between comprehensible finitude and perceivable infinity, it feels frighteningly critical.

《Data Waves in the Rising Sun》by Wen New Atelier (Kalen Iwamoto & Julien Silvano)

Miniscriber by Wen New Atelier (Kalen Iwamoto & Julien Silvano)

Miniscriber is presented as a literary device for the digital age. This device, embedded in a small wooden box, features a display that shows text along with several buttons and knobs. This is a text synthesizer. Pressing the “INPUT” button allows you to switch between source texts. These texts are two writings about the nature of writing in the contemporary era. By turning knobs and pressing buttons on this text, new text can be created. As an artwork, it’s important for viewers to physically experience this. The possible operations include “ERASURE,” which blacks out random words; “CUTUP,” which displays frames that selectively read out random words; “ASCII NOISE,” which replaces random characters with noise-like symbols; “WAVEFORM,” which shifts text positions like waves; “HIGHLIGHT,” which randomly changes text colors; and “ITALIC,” which italicizes text. These operations merely manipulate the source text—you cannot add your own characters. This feels like taking a bird’s-eye view of text creation in the contemporary era. Additionally, the modulation and noise application have rhythm, and the fact that they continuously flow according to this rhythm also symbolizes the spirit of our times. This work also questions the relationship between reader and writer, blurring their boundaries. …At the exhibition, I sometimes saw the device continuously generating text unread by anyone in a quiet, dark room. There was something lonely about it, a scene that also made one think about the fate of overproduced text.

Predeterminate, yet unknown by michelangelo (encapsuled)

michelangelo (encapsuled) is an Italian artist who works with both conventional language and asemic language (meaningless language). In this exhibition, he presents two generative works. These works are NFTs that record JavaScript code.

In one of them, Predeterminate, yet unknown, flowing lines resembling cursive writing wrap around lines and scroll endlessly. The exhibition display, with a monitor installed on an aluminum frame mimicking a loom, appeared as if it were in the midst of spinning threads to create words. The title, which literally means ‘predetermined, yet unknown,’ reveals its true significance when we examine the code inside. While I don’t know whether the artist wants viewers to look at the internal code, it is publicly available, and since I found something very important within it, I’d like to actively introduce it here. The movement of these character-like lines is generated from three random seeds. These are: the current time at execution, the past time from 10 seconds ago, and the future time 10 seconds ahead. The time is UNIX time, common in the computer world, sampled at 10-second intervals, with its hash value serving as the random seed. In other words, this generative art is designed so that the exact same thing will be displayed on any computer, with an error margin of within 10 seconds. Isn’t this work concept born from thinking unique to our contemporary era where computers and the internet have become widespread? When we unravel the drawing algorithm, we also discover that what’s visible is not the entirety of the internal structure. Line segments generated from future time tend to appear probabilistically in upper positions within a line, while conversely, those from past time tend to appear in lower positions. These “candidates” for brush strokes are observed in sync with the auto-scrolling timing, and only line segments containing points within a specific range are drawn. At this moment, present, future, and past overlap as one in a kind of shadow-like form. The processing that produces complex results from simplicity makes the drawing content difficult to predict, creating a state that is “predetermined” yet remains “unknown” until actually seen.

Numerous attempts to explore the boundary between meaninglessness and meaning, called asemic writing, have been made historically. However, among these, I believe this work is particularly valuable in that it preserves the thinking process in tangible form. It demonstrates compelling effectiveness beyond mere speculation.

Predeterminate, yet unknown by michelangelo (encapsuled)

Just like you by michelangelo (encapsuled)

Just like you is a generative work written in JavaScript like Predeterminate, yet unknown, sharing the common feature of reconstructing its drawing based on universal time every 10 seconds. Thin white lines emerge against a dark background, slowly generating and disappearing. While the work is introduced as an “endless never repeating animation,” examining the internal code reveals that this “endlessness” is supported by a cyclical structure of time.

In this work, a string generated from the current UTC time is hashed with SHA256, and that value is used as two random seeds. This ensures that the same composition is output on all browsers at the same time. The drawing mechanism starts from coordinate points arranged at regular intervals, with short line segments drawn with gentle directional changes. When a line exceeds a certain distance, it automatically stops and transitions to the next line. Overall, it repeats fade-in and fade-out in 10-second cycles, with a vertical line appearing briefly near the center, blinking like a cursor. These movements can be seen as a visualization of the process of “writing, thinking, erasing, writing again.”

The title ‘Just like you’ suggests that just as humans think, hesitate, and start over, this program also internally repeats decisions and regeneration. The unobservable internal state exists with certainty while remaining invisible, like the inside of consciousness. This work is an attempt to reconstruct the conditions of “how thought occurs” through code. Viewers find themselves facing another existence that continues to write quietly.

What makes michelangelo (encapsuled) unique in the context of asemic writing is that he doesn’t just draw meaningless characters, but writes “code that performs the generation of meaning itself.” In his works, both brushwork and grammar autonomously emerge within algorithms, and the boundary between what is written and what is not written wavers within calculation. If asemic writing questions the limits of human handwriting, his attempt reopens the question of “who is writing” through the non-human writing apparatus of code.å

Just like you by michelangelo (encapsuled)

MONEY by Nahiko

This work is created as an NFT that returns HTML containing an image as metadata. When the HTML is opened in a browser, it displays an image of a faceless figure sitting on what appears to be a destroyed gravestone. In the center is a button labeled “MONEY.” Pressing the button brings up a CAPTCHA authentication screen showing distorted “money” text. After typing this on the keyboard and pressing the button again, a dialog for printing the page appears. If you cancel this (though you could certainly proceed with printing), the HTML page transforms with beeping sounds, becoming filled with pop-ups and window-like elements all labeled “MONEY.” Finally, a screen displaying only the plain text “MONEY” appears. This process seems to erode the HTML structure itself, reminiscent of net art from the 2000s.

The PNG format image contained in the HTML has the byte sequence “MONEY” embedded through steganography techniques. Within the HTML/JS code itself, the string “MONEY” is embedded in countless places. In the NFT’s smart contract too, digital “MONEY” is embedded through various methods in every conceivable location: license notations in the source code, security contact email addresses, contract names, variable names, constant values, event names, function return values, interfaces, file names, error messages, and more. In the exhibition display, a desk with a PC and three monitors was installed with a chair, and a plastic bottle with half-drunk water was casually placed there, as if Nahiko had just been present. The three monitors displayed: a browser with the HTML file open, a binary editor with the image file open, and the NFT smart contract’s page on Etherscan.

Nahiko presents these words, omnipresent in every location, as the artwork itself, calling this an “omnipoem”. The word “MONEY” is embedded in different forms within code, HTML, images, data, and smart contract internals. This work reveals that what we call “digital” actually operates through mutually different principles and methods of description.

MONEY expands the meaning of code poetry, bringing to light the unique linguistic qualities possessed by each medium that constitutes the digital. Code, images, markup, APIs, user interfaces—the single word “MONEY” penetrates through each of these, all operating on different principles. This word functions not only as meaning but also actually works within economic and technological contexts. Here, Nahiko discovers the possibility of poetry emerging within the composite medium of digital artifacts.

MONEY by Nahiko

Imperceptible Aesthetics – Quantumf*ck [16 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

In this exhibition, artist Akihiro Kubota undertook a new dimensional challenge in computation and poetry, calling it “quantum computational poetry.” This is a quantitative exploration and poetic interpretation of aesthetic states using quantum computers. The calculations using actual quantum computers in this endeavor were conducted with the cooperation of the Center for Quantum Information and Quantum Biology (QIQB) at Osaka University.

Quantum computers are a new type of computer being developed for practical use, and quantum bits (qubits), which can hold and compute states between 0 and 1, enable calculations on computers that were previously impossible. But what kind of world is this, and what operations can be performed? An environment for everyone to experientially understand this has not yet been sufficiently established. In response to this situation, Kubota developed two small programming languages for operating quantum computers. These are the new quantum programming languages “Quantumf*ck”1 and “INTRACAL”2, referencing “Brainf*ck” created in 1993 and “INTERCAL” created in 1972. While each has different syntax and distinctive humorous specifications, what they share is the ability to perform basic operations on qubits at the minimal unit level. Furthermore, along with developing these languages, Kubota constructed “quantum information aesthetics”3 as a theoretical foundation. This extends the “information aesthetics” proposed by German philosopher and aesthetician Max Bense in the 1950s-60s to objects in quantum states. Quantum information aesthetics approaches the question “What constitutes an aesthetic quantum state?” from quantum information theory, proposing the idea that states where four indicators—“order,” “complexity,” “quantum uncertainty,” and “classical uncertainty”—achieve high values in good balance are considered “aesthetic.”

What Kubota presented as artworks in this exhibition are code poems written in the two quantum programming languages he developed, and graphical poems created from the results of executing and measuring these on actual quantum computers.

Imperceptible Aesthetics – Quantumf*ck [16 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

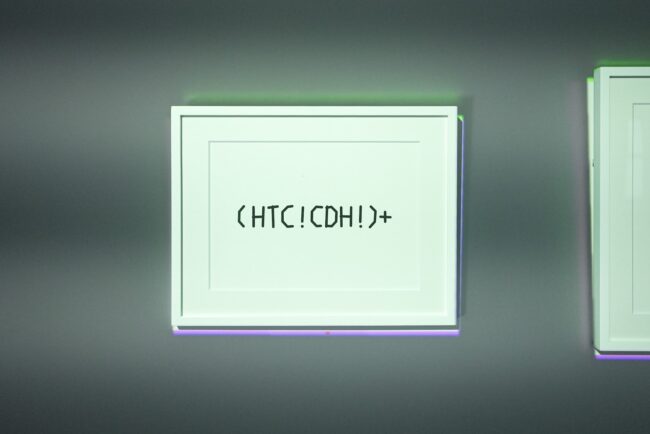

Imperceptible Aesthetics – Quantumf*ck [16 Qubits] is a code poem written in the Quantumf*ck language. The referenced Brainf*ck is a minimal programming language that can write basic commands to add or subtract values to an array of multiple addresses that can hold numerical values. In contrast, Quantumf*ck is aå language that can perform operations on an array of qubits, such as creating superposition states, rotating phases, flipping bits, and performing operations that can create entangled states. Furthermore, this language incorporates an expansion function using regular expressions, referencing the poetic programming language Coem.

What is written in this poem is one or more repetitions of operations that bring the qubit array into an aesthetic state and operations that reverse it. In Kubota’s quantum information aesthetics experiments, it has been confirmed that repeating the operations of “superposition + rotation + entanglement” creates highly aesthetic states. In the first half of this code, “HTC” creates an aesthetic state, and “!” randomly moves to another qubit. The subsequent “CDH” performs the reverse operation, and “!” randomly moves again. This is what Kubota calls an “inverse aesthetic quantum circuit,” which seems to have been originally introduced to measure and verify aesthetic states, but by being incorporated into code poetry, it creates a fleeting poetic quality where aesthetic states are generated and then disappear. However, uncertainty created by the regular expression expansion function and operations that randomly move qubits are also added. By combining with classical fluctuations, aesthetic states are not simply cancelled out but also influence subsequent entanglements, creating complex states. This poem harbors infinite possibilities within its brevity.

Imperceptible Aesthetics – INTRACAL [8 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

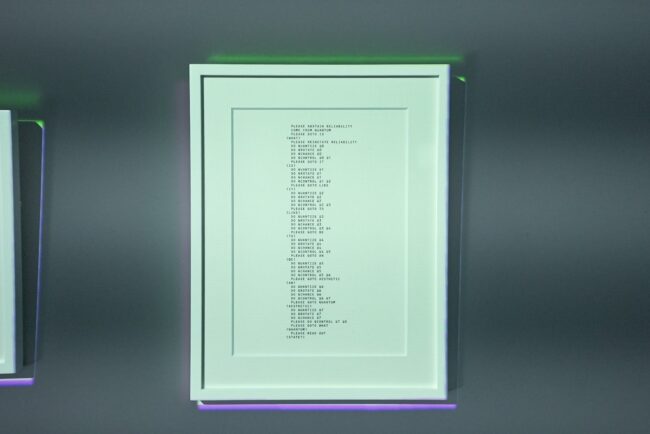

Imperceptible Aesthetics – INTRACAL [8 Qubits] is a code poem written in another quantum programming language, INTRACAL.

The referenced INTERCAL is an extremely humorous programming language that upholds “Politeness” toward computers as its design philosophy. You can write the syntax “PLEASE” before commands, and if this ratio isn’t above a certain level, the computer won’t execute the code. Conversely, if the ratio becomes too high, the computer gets fed up and stops execution. INTRACAL follows the same philosophy and, like Quantumf*ck, has commands for performing basic operations on qubits. For example, “QUANTIZE @q” puts the q-th qubit into superposition state, “QROTATE @q” performs rotation (phase addition), and “QCONTROL @c @t” creates entanglement (applies a controlled NOT gate, which can create entangled states). As poetic elements, there’s also “QCHANCE” which flips a qubit with 50% probability (applies an X gate), “QRANDOM” which randomly applies one of several operations, and “ABSTAIN RELIABILITY” for entering “unreliable mode” where all commands randomly fail with 15% probability. It also inherits “COME FROM,” the reverse of “GOTO,” which is familiar in INTERCAL.

The code poem in INTRACAL presented here uses each word from the sentence “What is it like to be an Aesthetic Quantum State?” as labels. The processing for each label basically consists of operations that bring qubits into aesthetic states, and these are repeatedly executed as a whole while also using the aforementioned “unreliable mode.” Since random commands are inserted throughout, results vary with each execution, but the computer eventually stops processing because the ratio of “PLEASE” gradually decreases among the total steps being executed. This poem quotes the spirit and culture of INTERCAL, one of the earliest Esolangs (esoteric programming languages)—going against well-known programming languages of its time, anti-pragmatism, questioning the formal correctness of always returning the right answer—and represents resistance that seeks to rediscover the raw potential inherent in computers within the world of quantum programming, a beacon of hope in the contemporary era.

Multiple Shadows – 2025.09.02 12:16:56 [16 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

Multiple Shadows – 2025.09.02 12:16:56 [16 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

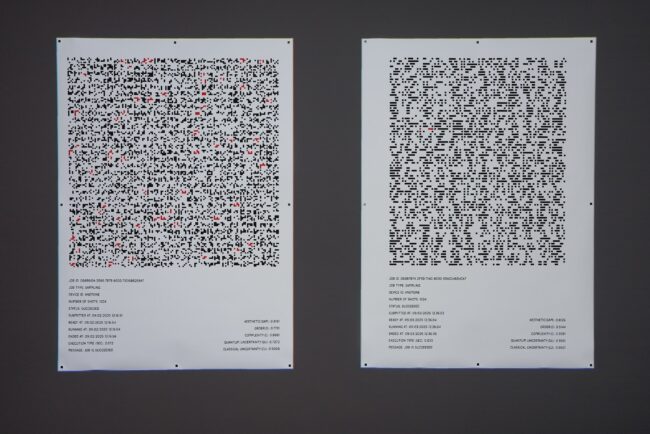

This work is a graphical poem created from the results of measuring qubits after executing Imperceptible Aesthetics – Quantumf*ck [16 Qubits] on QIQB’s superconducting quantum computer. Sixteen qubits were used, sampled 1024 times. When the previous code poem is executed, the regular expression “one or more repetitions” is randomly expanded (internally using Python libraries used in live coding), and based on this, each qubit is operated on in sequence. When the state of each qubit is finally measured, 16 classical bit results of 0 or 1 are obtained. This graphical poem arranges these results in a 4×4 grid. In a sense, this is a visible result. Below, the quantum aesthetic velocity value calculated from the state including its internal structure is written. The value is 0.8181, which appears to be in the relatively beautiful category.

While presented as a “graphical poem,” what’s interesting is that the visible results here are not the quantum bit states themselves, but observational results with considerable information stripped away. Since the qubit operations in this code don’t create bias in the probabilities between 0 and 1, the observational results are utterly singular. There’s no reproducibility here, and no matter how much you visualize it, it would be difficult to say anything objective (however, in this execution, one result of the expanded regular expression is sampled 1024 times, so there is bias in that single expansion result. In this sense, the visible results are strongly influenced by classical randomness). On the other hand, the quantum aesthetic velocity value written below provides a clue for discussing the beauty of invisible parts. This includes values that can only be obtained from quantum computer simulations. This is an unavoidable aspect due to the nature of quantum mechanics, confronting us with the reality that not everything can be formalized. But perhaps that is precisely what beauty is.

Multiple Shadows – 2025.09.03 12:36:05 [8 Qubits] by Akihiro Kubota

This work is a graphical poem created from the results of measuring qubits after executing another code poem, “Imperceptible Aesthetics – INTRACAL [8 Qubits],” on QIQB’s superconducting quantum computer. Eight qubits were used, sampled 1024 times. This too is based on a series of qubit operations where results change with each execution. In this graphical poem, the results of eight classical bits are arranged as black and white bars in a single line. Between each bit in these visible bars, quantum entanglement states that mutually influence each other were created, though invisible to the eye. This is precisely the fruit of what Karen Barad conceives as intra-action. And it existed with certainty as something physical in the real world. Imagining this, we gain a tangible sense that the quantum world is not a fantasy from a distant land, but exists in the same world as something we can perceive right here and now.

Left: Multiple Shadows – 2025.09.02 12:16:56 [16 Qubits] Right: Multiple Shadows – 2025.09.03 12:36:05 [8 Qubits]

Random Rain 2025 by Akihiro Kubota

To understand this work, one must know about Befunge, a peculiar programming language. Befunge is an experimental stack-based programming language created in 1993, which executes by moving through two-dimensional source code in all four directions. This language was originally created to be something that couldn’t be compiled—that is, something whose results couldn’t be predicted until executed. The language also serves as a critique of how conventional programming languages are confined to one-dimensional linear syntax (left to right, top to bottom).

In 2019, Kubota wrote a poem using this Befunge language. This poem reinterprets through code the concrete poem Rain by avant-garde poet Seiichi Niikuni, who similarly questioned one-dimensional syntax in the 1960s. Rain places the kanji character for “rain” (雨) at the bottom center, with the dot elements from the character densely scattered around it. Here, the kanji’s meaning is deconstructed, and its fundamental semantic image merges with the visual image created by the two-dimensional spatial arrangement. The code poem written in Befunge transplants this into an executable dimension. The rain character’s dot elements are replaced with “?” commands, behaving as meaningful symbols that “randomly redirect the execution position.” The execution position moves freely in all directions like a gaze. Eventually, when it reaches specific positions at the bottom, the string “Rain.” is pushed onto the stack character by character, then output character by character with conditional branching and elegant movement, before processing stops. Every character has meaning.

What was exhibited in this show is a 2025 version recreation of this earlier work4. The main change is that two types of poem source code with different densities of “?” are generated in random arrangements each time. This is built upon double randomness, offering implications for the relationship between algorithms and their products, and the nature of media art works. A Python interpreter was also implemented specifically for this exhibition, paying respect to the original 1993 Befunge language specifications. The fixed source code grid size of 80×25 also derives from this. This echoes how concrete poems created through phototypesetting were made under physical size constraints. A global language that takes words as material, where arrangement creates meaning—this is a poem that straightforwardly embodies what concrete poetry sought to achieve.

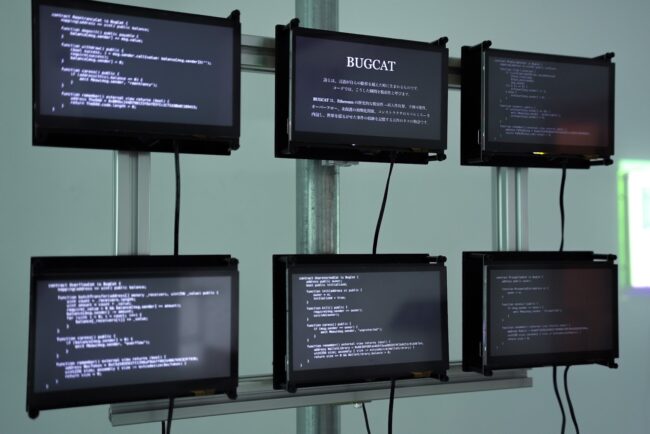

BUGCAT by Zeroichi Arakawa

BUGCAT is a code poem written in Solidity, a programming language for smart contracts, and a literary work deployed on the Ethereum blockchain. The history of Ethereum exists alongside smart contract vulnerabilities. Many unexpected bugs have led to massive asset hackings. These have forced projects and services to shut down, divided chains and communities, and generated emotions of anger, sadness, and disappointment. ”BUGCAT“ is a poem built upon Solidity’s culture and history, to face, accept, and remember such realities.

There are five poems, each implementing historically known vulnerabilities in minimal, executable form. Each is shaped and named as a cat, referencing actual smart contracts that were hacked through these vulnerabilities. The reference here isn’t merely conceptual but live—it actually calls the smart contracts at those addresses and verifies the existence of their bytecode. This is possible thanks to the unique environment of blockchain. Blockchain is a public execution environment that gives existence to digitally created things.

The unexpected behaviors occurring within these cats harbor a structural beauty that cannot be fully expressed by the phrase “algorithmic beauty.” For example, ReentrancyCat is a cat susceptible to recursive hacking attacks where, when calling a function to withdraw deposited crypto assets, the fallback function that automatically executes upon receiving crypto assets can call the withdrawal function again. When this happens, unexpected crypto assets flow out endlessly, as if blood were flowing from the cat. This isn’t simply about recursive calling—conditional branching to stop the bleeding midway is also necessary. This behavior doesn’t occur from the cat’s code alone but requires interaction with the calling code. Reading comprehension and a kind of poetry creation by the reader are essential. As another example, OverflowCat, when calling a function to send internally created tokens, causes overflow when passing 2 to the 256th power—an extremely large number—as the sending amount to two or more recipients, multiplying these values. This bypasses the caller’s token balance check, alchemically creating tokens that shouldn’t exist. Tokens born from nothing are both false value and surprising events beyond the author’s intention. In this example too, hacking cannot be accomplished by the cat alone—the caller must read the code and send a transaction with specific parameters. In other words, for these works to function, the code must be read. Such code-based works are resistance against the many opaque systems prevalent today. For the other three cats as well, please decode their code poems, meanings, and hacking methods from the BUGCAT website5.

BUGCAT by Zeroichi Arakawa

Executed Poetry by Zeroichi Arakawa

Attempts to write poetry with code have existed since the 1960s. Such works are called code poetry. However, no standard method for exhibiting these works has been established. Moreover, there has been little discussion about what constitutes the work in code poetry. Should what be recognized as the work be the code text itself, the result of executing the code, the internal state during execution, the executing process, or perhaps the executing computer, or the display showing it? Executed Poetry6 presents one solution to such questions. Here, the code poetry text, a Raspberry Pi Pico computer serving as the execution environment, the executable state, a button to start execution, Python files stored in the computer’s built-in flash memory, and an e-paper display showing the file contents and execution results are all packaged together as one unit. This is a book-like format for code poetry. The entirety is presented as the work.

This work consists of six code poems exhibited in this format. The code ranges from 2 to 6 lines, written in Python. Each poem actively uses Python-specific syntax and standard features. Python was created under the philosophy that there should be one—and preferably only one—obvious way to do something (see “Zen of Python” for details). In recent years, it has become the representative language for fields seeking practicality and efficiency, such as AI research and data analysis. Executed Poetry defies such “one obvious way,” expanding the scope of thinking through code by considering directions different from practical use. For example, in one poem “If your heart is empty, borrow love from the universe,” it attempts to import a non-existent module “love” and fails. That error is caught by “except Exception as love,” treated as the variable “love,” and then added to “heart.” An error that should normally be removed is here accepted as-is and remembered. Also, the “love” module might exist depending on the environment. In that case, no error occurs but “heart” remains empty. Deviation and ambiguity can be created within short code. This is precisely poetry, and the dimension of execution is an important element for contemporary thinking. This work demonstrates such simple examples.

Now, in this format, three pieces of information—“msg,” “pub,” and “sig”—are displayed small at the bottom of the e-paper. This is the result of digital signature by this computer. This small computer has a device-specific ID, based on which an Ed25519 key pair is internally generated. “msg” is the signed data, containing the number of times the poem was executed, the processing time, and the poem’s title. In other words, proof that this computer executed that poem is shown there. This mechanism exists to recognize the execution environment of code poetry works as real existence. These poems can certainly be executed and affect our world. The changes occurring within the small computer and the e-paper updates are small but certain presences for experiencing that possibility.

Executed Poetry by Zeroichi Arakawa

CodeTEI by Zeroichi Arakawa

If Executed Poetry demonstrates a physical work format for code poetry, then CodeTEI7 demonstrates a work format as data. Code-based works such as code poetry have primarily been presented on authors’ websites, social media like X, forums like PerlMonks8, and events like Code Poetry Slam9 and Code Poetry Challenge10. However, from the perspective of preserving works, these places and methods are fragile and ephemeral. While some have been published as poetry collections, these naturally cannot be executed. Code-based works should be handled including language versions, execution environments, execution state records, execution history, and information about people who interacted with them. CodeTEI extends TEI (Text Encoding Initiative)11, a document description standard widely used in literary research and digital humanities, to record these elements as part of the work. TEI is originally an international standard for describing the structure, annotations, and editorial history of literary works and historical documents in XML format, providing methodology for making computers read text structures such as poetry, drama, and novels. Adding the dimension of execution to this could be considered inevitable in contemporary times.

In this exhibition, it was proposed to treat this standard itself as poetry. CodeTEI is a format for rescuing code-based works from within digital space. Finding works, creating XML files according to this format, and contributing to preservation—isn’t this essentially synonymous with writing poetry? The exhibition displayed, as examples on two posters, website UIs of works that can be described by CodeTEI and their XML data. Archiving code poetry works according to such standards is extremely important for digital works that disappear unnoticed, and the author is dedicated to this effort.

“CodeTEI” by Zeroichi Arakawa

Conclusion: Referring to Sound Poetry: The Voice of Time

As a reference work in this exhibition, concrete poetry by poet Shigeru Matsui was displayed. Sound Poetry: Voice of Time is a work presented in 2019, and the panel of the poem titled Zone of Terror was created for an exhibition held at photographers’ gallery in 200912. This work was originally written to put an end to the manifesto of the Noigandles group, which led the movement, against the background of research into the international concrete poetry movement. That manifesto called for the realization of “verbivocovisual” (a neologism by James Joyce meaning the trinity of “verbal, vocal, and visual”). Interestingly, however, far from putting an end to concrete poetry, “Sound Poetry: Voice of Time” has continued to be exhibited and reinterpreted in various exhibitions and performances, continuously expanding the interpretation of what concrete poetry is. I personally think the significance of exhibiting this work in Computational Poetry may lie in adding interpretation within the context of computers and poetry.

To explain how this poem was written: the process involved recording and editing concrete sounds, listening to them and recording them as pronounced words, listening to these again and transcribing them as written text, then creating panels—each step performed by different people. Furthermore, there exists a poetry collection made by photographing these panels. Poetry creation is performed by multiple people, with each successive medium repeatedly encompassing the content of the previous one. In this sense, the works in this exhibition—poetry creation through code, continuously reconstructing text from literary quotations, continuously generating asemic language with code, reinterpreting concrete poetry through code, standards for recording code works—may also exist within this repetition where code as a new medium encompasses previous content.

“Voice of Time” finds its novelty in incorporating the materiality of words into the poetry creation process itself. What’s interesting is that the code poetry presented here similarly harbors meaning in invisible parts. The series of transformation processes performed in “Voice of Time” can be interpreted not as predefined procedures but as “computation not yet coded.”

Writing poetry using code—this means both increasing the resolution of poetry generation and exercising imagination about the invisible. Computational Poetry is not about computation itself as a goal, but an attempt to think about how to compute the uncomputable. And poetry always functions as a margin that code cannot reach.

- https://github.com/hemokosa/quantumfuck

- https://github.com/hemokosa/INTRACAL

- https://www.qst.go.jp/site/entangle-moment/exhibition-sec1.html

- https://github.com/hemokosa/random-rain2025

- https://bugcat.org

- https://executed-poetry.poesy.run

- https://github.com/CodeArtStudies/CodeTEI

- https://www.perlmonks.org

- https://engineering.stanford.edu/news/algorithms-meet-art-code-poetry-slam-held-stanford

- https://web.archive.org/web/20250614041948/https://www.sourcecodepoetry.com

- https://tei-c.org

- https://pg-web.net/exhibition/shigeru-matsui-glossolalia

Zeroichi Arakawa

Code Poet, Smart Contract Engineer.

Finding literary and structural beauty in program code, Zeroichi continues to explore and experiment with the values that emerge from code as a medium. Representative works include 《DeepSea》, which explores internal states through testing frameworks, and 《inside window》, which excavates poetic spaces hidden within the browser runtime environment. These works present both the importance of reading code itself and the poetic experiences generated through its execution. Currently pursuing a PhD at the Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS).